Like most radical ideas, the Garden City was born from extreme circumstances. As Britain’s 19th century industrial cities swelled with people, festered with pollution and teemed with disease, a reformer named Ebenezer Howard proposed a simple but artful solution: make cities smaller, and make them greener.

Like most radical ideas, the Garden City was born from extreme circumstances. As Britain’s 19th century industrial cities swelled with people, festered with pollution and teemed with disease, a reformer named Ebenezer Howard proposed a simple but artful solution: make cities smaller, and make them greener.

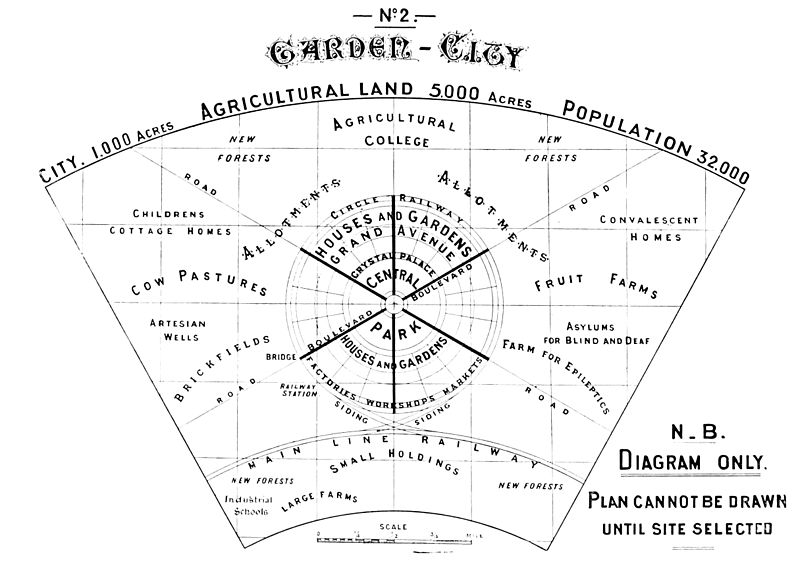

To achieve this, he proposed Garden Cities—hypothetical planned communities with no more than 32,000 residents on fewer than 10 square miles. Each would have a train station and small factories at its core, with boulevards radiating outward into neighborhoods with plentiful parks and gardens. Preserved farmland and forests on the outskirts would supply food and act as a buffer from other cities.

In Howard’s mind, a string of these Garden Cities, connected by rail and canal, would encircle every big city to absorb growing populations and provide urban dwellers with a delicate balance of town and country living. And every time a Garden City reached its 32,000 person limit, construction on the next Garden City would begin.

It was a neat concept, but no system of Garden Cities was ever built, in part because advances in housing, sanitation and engineering cured or quelled many of the big city problems that gave rise to the idea. But Howard’s vision did influence the design of several carefully planned communities in the U.S., from Shaker Heights near Cleveland to Forest Hills Gardens in Queens.

And elements of the Garden City, especially the careful integration of parks and gardens into a compact and relatively self-contained urban environment, are seeing renewed interest today. Not just as solutions to rapidly growing cities, but as solutions for places in transition—small spaces or entire neighborhoods that are struggling to find new purpose and a new role in the 21st century.

Why is the Garden City of particular relevance to Jamestown? For one, our city has the dimensions of Howard’s ideal city (30,000 people and a compact geography), making it a place where simple ideas can be tested at reasonable cost and with noticeable impact.

More important, though, Jamestown is a transitional city with many transitional spaces. Industrial and commercial buildings that need new uses; empty residential lots that need new caretakers; oversized or poorly designed infrastructure that needs rethinking—all are examples of Jamestown’s slow evolution from an industrial city in the Industrial Age to something new, different and still uncertain.

Many transitions are well underway and yielding fruit, from the growing Riverwalk, which turned the Chadakoin River from a hidden industrial sewer to an expanding recreational asset, to downtown buildings with new businesses and new residents.

Many other transitions still need to be imagined—an exciting task for Jamestown’s current generations to undertake. And the Garden City provides us with some fodder as we consider how to remake or reuse parts of our city.

In many places, for example, vacant residential lots are being reimagined as community gardens, places that serve as neighborhood gathering spots and local food generators. For Rust Belt cities in particular, where these lots are unlikely to be redeveloped under current market conditions, gardens are seen as an interim use that removes blight and restores land to a vital and productive purpose—something JRC and its partners are looking to jumpstart in Jamestown this year.

Other cities are finding ways to infuse underused space or infrastructure with a splash of green. In Chicago, a green roof was installed on City Hall to reduce the building’s energy consumption, reduce the “heat island” effect in Chicago’s Loop, provide a scenic break spot for city workers, and add color to the city’s skyline. Imagine something similar on Jamestown’s Tracy Plaza—transforming a mostly windswept and dull public space into plantings and gardens with verdant reflections in City Hall’s gold-tinted windows.

In New York City, an abandoned elevated railroad track was redeveloped as a raised linear park (the High Line), allowing users to experience the city from an unusual perspective while transforming a neighborhood liability into a neighborhood attraction. Imagine something similar on Jamestown’s Third Street Bridge. By removing a traffic lane and installing movable planters, a concept currently being studied by architect Don Harrington with support from Creating Healthy Places to Live, Work and Play, it could become a linear parkway linking downtown and the Westside with dramatic views of the city and Chadakoin Valley.

Or imagine countless places in the city that could be infused with new life and new purpose by finding relatively small, simple, and unexpected ways to integrate nature with the city—the essence of the Garden City. As we rediscover and reinterpret what’s around us, we might be surprised by what we already have.

–Peter Lombardi