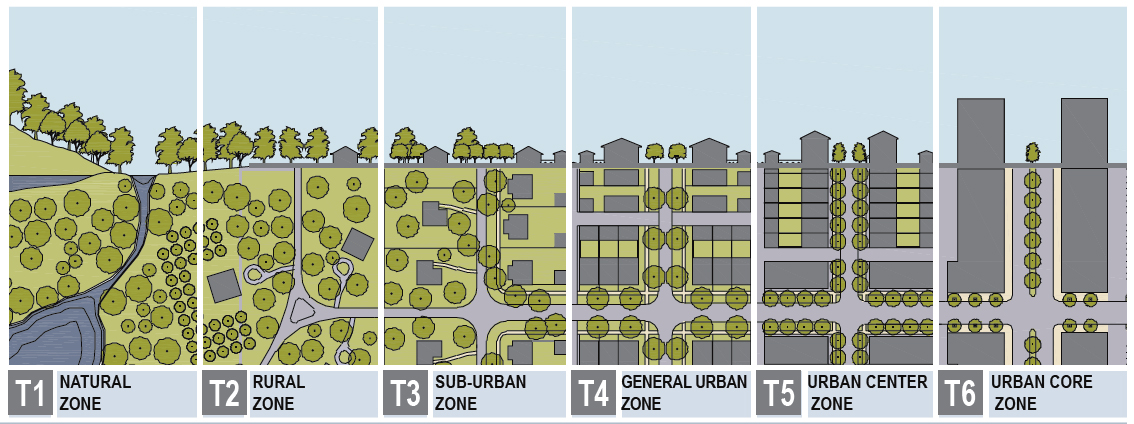

Form diagram of a residential district (N-3R) from Buffalo’s draft Unified Development Ordinance, an example of a form-based zoning code.

Huge shadows cast by a growing forest of skyscrapers. Overcrowded tenements next to smoke-belching factories. Garment sweatshops encroaching on the mansions of millionaires.

These and other pressures led to the adoption of America’s first citywide zoning ordinance 99 years ago in New York City. It was a revolutionary and controversial effort to control the nature of change in a city evolving at blistering speeds.

This experiment in controlling land use and development was mostly successful, creating a more predictable and orderly city. Interest groups as diverse as housing reformers, public health advocates, bankers, insurance companies, and real estate developers broadly agreed on the benefits of New York’s zoning code within a few years of its passage, including the separation of incompatible uses and the tapering of tall buildings – producing the distinctive silhouette of Art Deco skyscrapers.

Hundreds of other cities soon followed suit, spurred in part by advocacy from Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, a Stanford-trained engineer who saw zoning as a way to promote business through the protection of real estate assets.

Jamestown’s first zoning ordinance was passed in 1922. Simple in scope, it divided the city into two classes of district: business and residence. The following year, it was revised into three classes: residential, mercantile, and factory.

Amendments in 1955, 1969, and 1998 produced what we have today, with 11 zones that make distinctions between single-family, two-family, and multi-family housing, and several classes of commercial and industrial land uses.

As in most communities that were well established when zoning was introduced, Jamestown’s zoning ordinance had a limited impact at first. Because zoning districts largely reflected existing land use patterns, the ordinance had the effect of freezing those patterns in place. Uses that were incompatible to newly drawn districts were simply grandfathered to allow a fair transition to a new use at some point in the near or distant future.

The areas most influenced by the zoning ordinance were on the city’s periphery. Development there followed the use, setback, parking, and other regulations that were being incorporated into zoning codes throughout the U.S. These regulations, over time, led to the homogenous, car-oriented development patterns that shaped most of the country after the 1940s. Think of the difference between downtown Jamestown and today’s Brooklyn Square – an area largely developed in the 1970s – and you get an instant sense of how development has been shaped by zoning.

Many city planners now agree that conventional zoning codes are flawed. By strictly separating land uses, instituting minimum parking standards that often lead to acres of unnecessary pavement, and a number of other formulaic and often arbitrary restrictions, traditional zoning has become a barrier to redevelopment and a hindrance to the creation of healthy and vibrant communities. Places shaped by modern zoning tend to be ugly, uninspiring, and difficult to navigate without a personal vehicle.

In Jamestown or any city, flexibility is important. As markets and economies change, a city should be able to accommodate changes in how people live, work, shop, and move around. By keeping development patterns and land uses frozen, and by enforcing an urban form that ignores the human scale, traditional zoning has produced cities that resist change and opportunity.

Prohibiting a slaughterhouse from opening next to a house makes sense. Segregating all uses from each other, making it nearly impossible to live without a car, and hindering the reuse of buildings and land doesn’t make sense.

In his recent State of the City address, Mayor Sam Teresi called for a long overdue update of the city’s zoning ordinance. He’s right. As boring and inconsequential as zoning may seem, it has a huge influence on the future shape and function of every block and neighborhood.

Many cities are undertaking zoning reforms today, and many are looking in the direction of form-based codes. These are zoning and development codes that place less emphasis on how buildings and parcels are used and more emphasis on physical form and how a building fits in with its neighbors. The outcome of this approach – cities that are more beautiful and functional – is a step in the right direction.

It’s a step currently being followed in Buffalo, one of the largest cities in the country to develop a form-based code that incorporates goals from numerous citywide and neighborhood plans. To learn more about Buffalo’s efforts, visit www.buffalogreencode.com.

Jamestown has already shown an ability to adapt its zoning code in recent years through recognition of community gardening as a legitimate primary use of vacant lots – bringing flexibility to the reuse of land. By following the examples of communities now instituting form-based codes, it can go much further toward producing a place that is adaptive well into the future.

–Peter Lombardi

This post originally appeared in The Post-Journal on February 2, 2015, as the JRC’s biweekly Renaissance Reflections feature.